Stereoscopic Player (Commercial License) 1.6.2 serial key or number

Stereoscopic Player (Commercial License) 1.6.2 serial key or number

GStreamer 1.18.0 new major stable release | 2020-09-08 00:30 |

GStreamer 1.17.90 pre-release (1.18 rc1) | 2020-08-21 18:00 |

GStreamer Rust bindings 0.16.0 release | 2020-07-06 14:00 |

GStreamer 1.17.2 unstable development release | 2020-07-06 13:00 |

GStreamer 1.17.1 unstable development release | 2020-06-22 14:30 |

GStreamer Rust bindings 0.15.0 release | 2019-12-18 17:00 |

GStreamer 1.16.2 stable bug fix release | 2019-12-03 20:00 |

GStreamer Conference 2019 talk recordings online | 2019-11-06 14:00 |

GStreamer Conference 2019: Full Schedule, Talks Abstracts and Speakers Biographies now available | 2019-10-14 18:00 |

GStreamer 1.16.1 stable bug fix release | 2019-09-23 23:00 |

GStreamer Rust bindings 0.14.0 release | 2019-06-24 20:00 |

GStreamer Conference 2019 announced to take place in Lyon, France | 2019-06-12 14:00 |

GStreamer 1.14.5 stable bug fix release | 2019-05-31 23:00 |

GStreamer 1.16.0 new major stable release | 2019-04-19 11:00 |

Orc 0.4.29 bug-fix release | 2019-04-15 12:00 |

GStreamer 1.15.90 pre-release (1.16.0 release candidate 1) | 2019-04-11 08:00 |

GStreamer 1.15.2 unstable development release | 2019-02-27 10:00 |

GStreamer Rust bindings 0.13.0 release | 2019-02-22 15:00 |

GStreamer 1.15.1 unstable development release | 2019-01-18 00:30 |

GStreamer Conference 2018: Talks Abstracts and Speakers Biographies now available | 2018-10-09 13:30 |

GStreamer 1.14.4 stable bug fix release | 2018-10-02 23:30 |

GStreamer Conference 2018: Schedule of Talks and Speakers available | 2018-09-19 17:00 |

GStreamer 1.14.3 stable bug fix release | 2018-09-16 20:00 |

GStreamer 1.14.2 stable bug fix release | 2018-07-20 15:00 |

GStreamer Conference 2018 Announced | 2018-06-12 12:00 |

GStreamer 1.14.1 stable bug fix release | 2018-05-17 17:00 |

GStreamer 1.12.5 old-stable bugfix release | 2018-03-28 23:30 |

GStreamer 1.14.0 new major stable release | 2018-03-19 20:00 |

3D film

3D films are motion pictures made to give an illusion of three-dimensional solidity, usually with the help of special viewing devices (glasses worn by viewers). They have existed in some form since 1915, but had been largely relegated to a niche in the motion picture industry because of the costly hardware and processes required to produce and display a 3D film, and the lack of a standardized format for all segments of the entertainment business. Nonetheless, 3D films were prominently featured in the 1950s in American cinema, and later experienced a worldwide resurgence in the 1980s and 1990s driven by IMAX high-end theaters and Disney-themed venues. 3D films became increasingly successful throughout the 2000s, peaking with the success of 3D presentations of Avatar in December 2009, after which 3D films again decreased in popularity.[1] Certain directors have also taken more experimental approaches to 3D filmmaking, most notably celebrated auteurJean-Luc Godard in his film 3x3D.

History[edit]

Before film[edit]

The basic components of 3D film were introduced separately between 1833 and 1839. Stroboscopic animation was developed by Joseph Plateau in 1832 and published in 1833 in the form of a stroboscopic disc, which he later called the fantascope and became better known as the phénakisticope. Around the very same time (1832/1833), Charles Wheatstone developed the stereoscope, but he didn't really make it public before June 1838. The first practical forms of photography were introduced in January 1839 by Louis Daguerre and Henry Fox Talbot. A combination of these elements into animated stereoscopic photography may have been conceived early on, but for decades it did not become possible to capture motion in real-time photographic recordings due to the long exposure times necessary for the light-sensitive emulsions that were used.

Charles Wheatstone got inventor Henry Fox Talbot to produce some calotype pairs for the stereoscope and received the first results in October 1840. Only a few more experimental stereoscopic photographs were made before David Brewster introduced his stereoscope with lenses in 1849. Wheatstone also approached Joseph Plateau with the suggestion to combine the stereoscope with stereoscopic photography. In 1849, Plateau published about this concept in an article about several improvements made to his fantascope and suggested a stop motion technique that would involve a series of photographs of purpose-made plaster statuettes in different poses.[2] The idea reached Jules Duboscq, an instrument maker who already marketed Plateau's Fantascope as well as the stereoscopes of Wheatstone and Brewster. In November 1852, Duboscq added the concept of his "Stéréoscope-fantascope, ou Bïoscope" to his stereoscope patent. Production of images proved very difficult, since the photographic sequence had to be carefully constructed from separate still images. The bioscope was no success and the only extant disc, without apparatus, is found in the Joseph Plateau collection of the University of Ghent. The disc contains 12 albumen image pairs of a machine in motion.[3]

Most of the other early attempts to create motion pictures also aimed to include the stereoscopic effect.

In November 1851, Antoine Claudet claimed to have created a stereoscope that showed people in motion.[4] The device initially only showed two phases, but during the next two years, Claudet worked on a camera that would record stereoscopic pairs for four different poses (patented in 1853).[5] Claudet found that the stereoscopic effect didn't work properly in this device, but believed the illusion of motion was successful.[6]

Johann Nepomuk Czermak published an article about his Stereophoroskop. His first idea to create animated images in 3D involved sticking pins in a stroboscopic disc in a sequence that would show the pin moving further into the cardboard and back. He also designed a device that would feed the image pairs from two stroboscopic discs into one lenticular stereoscope and a vertical predecessor of the zoetrope.[7]

On 27 February 1860 Peter Hubert Desvignes received British patent no. 537 for 28 monocular and stereoscopic variations of cylindrical stroboscopic devices. This included a version that used an endless band of pictures running between two spools that was intermittently lit by an electric spark.[8] Desvignes' Mimoscope, received an Honourable Mention "for ingenuity of construction" at the 1862 International Exhibition in London.[9] It could "exhibit drawings, models, single or stereoscopic photographs, so as to animate animal movements, or that of machinery, showing various other illusions."[10] Desvignes "employed models, insects and other objects, instead of pictures, with perfect success." The horizontal slits (like in Czermak's Stereophoroskop) allowed a much improved view, with both eyes, of the opposite pictures.[11]

In 1861 American engineer Coleman Sellers II received US patent No. 35,317 for the kinematoscope, a device that exhibited "stereoscopic pictures as to make them represent objects in motion". In his application he stated: "This has frequently been done with plane pictures but has never been, with stereoscopic pictures". He used three sets of stereoscopic photographs in a sequence with some duplicates to regulate the flow of a simple repetitive motion, but also described a system for very large series of pictures of complicated motion.[12][13]

On 11 August 1877, the Daily Alta newspaper announced a project by Eadward Muybridge and Leland Stanford to produce sequences of photographs of a running horse with 12 stereoscopic cameras. Muybridge had much experience with stereo photography and had already made instantaneous pictures of Stanford's horse Occident running at full speed. He eventually managed to shoot the proposed sequences of running horses in June 1878, with stereoscopic cameras. In 1898, Muybridge claimed that he had soon after placed the pictures in two synchronized zoetropes and placed mirrors as in Wheatstone's stereoscope resulting in "a very satisfactory reproduction of an apparently solid miniature horse trotting, and of another galloping".[14]

Thomas Edison demonstrated his phonograph on 29 November 1877, after previous announcements of the device for recording and replaying sound had been published earlier in the year. An article in Scientific American concluded "It is already possible, by ingenious optical contrivances, to throw stereoscopic photographs of people on screens in full view of an audience. Add the talking phonograph to counterfeit their voices and it would be difficult to carry the illusion of real presence much further". Wordsworth Donisthorpe announced in the 24 January 1878 edition of Nature that he would advance that conception: "By combining the phonograph with the kinesigraph I will undertake not only to produce a talking picture of Mr. Gladstone which, with motionless lips and unchanged expression shall positively recite his latest anti-Turkish speech in his own voice and tone. Not only this, but the life size photograph itself shall move and gesticulate precisely as he did when making the speech, the words and gestures corresponding as in real life."[15] A Dr. Phipson repeated this idea in a French photography magazine, but renamed the device "Kinétiscope" to reflect the viewing purpose rather than the recording option. This was picked up in the United States and discussed in an interview with Edison later in the year.[16] Neither Donisthorpe or Edison's later moving picture results were stereoscopic.

Early patents and tests[edit]

In the late 1890s, British film pioneer William Friese-Greene filed a patent for a 3D film process. In his patent, two films were projected side by side on screen. The viewer looked through a stereoscope to converge the two images. Because of the obtrusive mechanics behind this method, theatrical use was not practical.[17]

Frederic Eugene Ives patented his stereo camera rig in 1900. The camera had two lenses coupled together 13⁄4 inches (4.45 centimeters) apart.[18]

On June 10, 1915, Edwin S. Porter and William E. Waddell presented tests to an audience at the Astor Theater in New York City.[19] In red-green anaglyph, the audience was presented three reels of tests, which included rural scenes, test shots of Marie Doro, a segment of John Mason playing a number of passages from Jim the Penman (a film released by Famous Players-Lasky that year, but not in 3D), Oriental dancers, and a reel of footage of Niagara Falls.[20] However, according to Adolph Zukor in his 1953 autobiography The Public Is Never Wrong: My 50 Years in the Motion Picture Industry, nothing was produced in this process after these tests.

1909–1915: Alabastra and Kinoplastikon[edit]

By 1909 the German film market suffered much from overproduction and too much competition. German film tycoon Oskar Messter had initially gained much financial success with the Tonbild synchronized sound films of his Biophon system since 1903, but the films were losing money by the end of the decade and Messter would stop Tonbild production in 1913. Producers and exhibitors were looking into new film attractions and invested for instance in colorful imagery. The development of stereoscopic cinema seemed a logical step to lure visitors back into the movie theatres.

In 1909, German civil engineer August Engelsmann patented a process that projected filmed performances within a physical decor on an actual stage. Soon after, Messter obtained patents for a very similar process, probably by agreement with Engelsmann, and started marketing it as "Alabastra". Performers were brightly dressed and brightly lit while filmed against a black background, mostly miming their singing or musical skills or dancing to the circa four-minute pre-recorded phonographs. The film recordings would be projected from below, to appear as circa 30 inch figures on a glass pane in front of a small stage, in a setup very similar to the Pepper's ghost illusion that offered a popular stage trick technique since the 1860s. The glass pane was not visible to the audience and the projected figures seemed able to move around freely across the stage in their virtual tangible and lifelike appearance. The brightness of the figures was necessary to avoid see-through spots and made them resemble alabaster sculptures. To adapt to this appearance, several films featured Pierrot or other white clowns, while some films were probably hand-coloured. Although Alabastra was well received by the press, Messter produced few titles, hardly promoted them and abandoned it altogether a few years later. He believed the system to be uneconomical due to its need for special theatres instead of the widely available movie screens, and he didn't like that it seemed only suitable for stage productions and not for "natural" films. Nonetheless, there were numerous imitators in Germany and Messter and Engelsmann still teamed with American swindler Frank J. Goldsoll set up a short-lived variant named "Fantomo" in 1914.[21]

Rather in agreement with Messter or not, Karl Juhasz and Franz Haushofer opened a Kinoplastikon theatre in Vienna in 1911. Their patented system was very similar to Alabaster, but projected life-size figures from the wings of the stage. With much higher ticket prices than standard cinema, it was targeted at middle-class audiences to fill the gap between low-brow films and high-class theatre. Audiences reacted enthusiastically and by 1913 there reportedly were 250 theatres outside Austria, in France, Italy, United Kingdom, Russia and North America. However, the first Kinoplastikon in Paris started in January 1914 and the premiere in New York took place in the Hippodrome in March 1915. In 1913, Walter R. Booth directed 10 films for the U.K. Kinoplastikon, presumably in collaboration with Cecil Hepworth. Theodore Brown, the licensee in the U.K. also patented a variant with front and back projection and reflected decor, and Goldsoll applied for a very similar patent only 10 days later.[21] Further development and exploitation was probably haltered by World War I.

Alabastra and Kinoplastikon were often advertised as stereoscopic and screenless. Although in reality the effect was heavily dependent on glass screen projection and the films were not stereoscopic, the shows seemed truly three-dimensional as the figures were clearly separate from the background and virtually appeared inside the real, three-dimensional stage area without any visible screen.

Eventually, longer (multi-reel) films with story arcs proved to be the way out of the crisis in the movie market and supplanted the previously popular short films that mostly aimed to amuse people with tricks, gags or other brief variety and novelty attractions. Sound film, stereoscopic film and other novel techniques were relatively cumbersome to combine with multiple reels and were abandoned for a while.

Early systems of stereoscopic filmmaking (pre-1952)[edit]

The earliest confirmed 3D film shown to an out-of-house audience was The Power of Love, which premiered at the Ambassador Hotel Theater in Los Angeles on 27 September 1922.[22][23][24] The camera rig was a product of the film's producer, Harry K. Fairall, and cinematographer Robert F. Elder.[17] It was filmed dual-strip in black and white, and single strip color anaglyphic release prints were produced using a color film invented and patented by Harry K. Fairall. A single projector could be used to display the movie but anaglyph glasses were used for viewing. The camera system and special color release print film all received U.S Patent No. 1,784,515 on Dec 9, 1930.[25][26] After a preview for exhibitors and press in New York City, the film dropped out of sight, apparently not booked by exhibitors, and is now considered lost.

Early in December 1922, William Van Doren Kelley, inventor of the Prizma color system, cashed in on the growing interest in 3D films started by Fairall's demonstration and shot footage with a camera system of his own design. Kelley then struck a deal with Samuel "Roxy" Rothafel to premiere the first in his series of "Plasticon" shorts entitled Movies of the Future at the Rivoli Theater in New York City.

Also in December 1922, Laurens Hammond (later inventor of the Hammond organ) premiered his Teleview system, which had been shown to the trade and press in October. Teleview was the first alternating-frame 3D system seen by the public. Using left-eye and right-eye prints and two interlocked projectors, left and right frames were alternately projected, each pair being shown three times to suppress flicker. Viewing devices attached to the armrests of the theater seats had rotary shutters that operated synchronously with the projector shutters, producing a clean and clear stereoscopic result. The only theater known to have installed Teleview was the Selwyn Theater in New York City, and only one show was ever presented with it: a group of short films, an exhibition of live 3D shadows, and M.A.R.S., the only Teleview feature. The show ran for several weeks, apparently doing good business as a novelty (M.A.R.S. itself got poor reviews), but Teleview was never seen again.[27]

In 1922, Frederic Eugene Ives and Jacob Leventhal began releasing their first stereoscopic shorts made over a three-year period. The first film, entitled Plastigrams, was distributed nationally by Educational Pictures in the red-and-blue anaglyph format. Ives and Leventhal then went on to produce the following stereoscopic shorts in the "Stereoscopiks Series" released by Pathé Films in 1925: Zowie (April 10), Luna-cy! (May 18), The Run-Away Taxi (December 17) and Ouch (December 17).[28] On 22 September 1924, Luna-cy! was re-released in the De ForestPhonofilm sound-on-film system.[29]

The late 1920s to early 1930s saw little interest in stereoscopic pictures. In Paris, Louis Lumiere shot footage with his stereoscopic camera in September 1933. The following March he exhibited a remake of his 1895 short film L'Arrivée du Train, this time in anaglyphic 3D, at a meeting of the French Academy of Science.[30]

In 1936, Leventhal and John Norling were hired based on their test footage to film MGM's Audioscopiks series. The prints were by Technicolor in the red-and-green anaglyph format, and were narrated by Pete Smith. The first film, Audioscopiks, premiered January 11, 1936, and The New Audioscopiks premiered January 15, 1938. Audioscopiks was nominated for the Academy Award in the category Best Short Subject, Novelty in 1936.

With the success of the two Audioscopiks films, MGM produced one more short in anaglyph 3D, another Pete Smith Specialty called Third Dimensional Murder (1941). Unlike its predecessors, this short was shot with a studio-built camera rig. Prints were by Technicolor in red-and-blue anaglyph. The short is notable for being one of the few live-action appearances of the Frankenstein Monster as conceived by Jack Pierce for Universal Studios outside of their company.

While many of these films were printed by color systems, none of them was actually in color, and the use of the color printing was only to achieve an anaglyph effect.[31]

Introduction of Polaroid[edit]

While attending Harvard University, Edwin H. Land conceived the idea of reducing glare by polarizing light. He took a leave of absence from Harvard to set up a lab and by 1929 had invented and patented a polarizing sheet.[32] In 1932, he introduced Polaroid J Sheet as a commercial product.[33] While his original intention was to create a filter for reducing glare from car headlights, Land did not underestimate the utility of his newly dubbed Polaroid filters in stereoscopic presentations.

In January 1936, Land gave the first demonstration of Polaroid filters in conjunction with 3D photography at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.[34][citation needed] The reaction was enthusiastic, and he followed it up with an installation at the New York Museum of Science.[citation needed] It is unknown what film was run for audiences at this exhibition.

Using Polaroid filters meant an entirely new form of projection, however. Two prints, each carrying either the right or left eye view, had to be synced up in projection using an external selsyn motor. Furthermore, polarized light would be largely depolarized by a matte white screen, and only a silver screen or screen made of other reflective material would correctly reflect the separate images.

Later that year, the feature, Nozze Vagabonde appeared in Italy, followed in Germany by Zum Greifen nah (You Can Nearly Touch It), and again in 1939 with Germany's Sechs Mädel rollen ins Wochenend (Six Girls Drive Into the Weekend). The Italian film was made with the Gualtierotti camera; the two German productions with the Zeiss camera and the Vierling shooting system. All of these films were the first exhibited using Polaroid filters. The Zeiss Company in Germany manufactured glasses on a commercial basis commencing in 1936; they were also independently made around the same time in Germany by E. Käsemann and by J. Mahler.[35]

In 1939, John Norling shot In Tune With Tomorrow, the first commercial 3D film using Polaroid in the US[citation needed]. This short premiered at the 1939 New York World's Fair and was created specifically for the Chrysler Motors Pavilion. In it, a full 1939 Chrysler Plymouth is magically put together, set to music. Originally in black and white, the film was so popular that it was re-shot in color for the following year at the fair, under the title New Dimensions.[citation needed] In 1953, it was reissued by RKO as Motor Rhythm.

Another early short that utilized the Polaroid 3D process was 1940's Magic Movies: Thrills For You produced by the Pennsylvania Railroad Co. for the Golden Gate International Exposition.[citation needed] Produced by John Norling, it was filmed by Jacob Leventhal using his own rig. It consisted of shots of various views that could be seen from the Pennsylvania Railroad's trains.

In the 1940s, World War II prioritized military applications of stereoscopic photography and it once again went on the back burner in most producers' minds.

The "golden era" (1952–1954)[edit]

What aficionados consider the "golden era" of 3D began in late 1952 with the release of the first color stereoscopic feature, Bwana Devil, produced, written and directed by Arch Oboler. The film was shot in "Natural Vision", a process that was co-created and controlled by M. L. Gunzberg. Gunzberg, who built the rig with his brother, Julian, and two other associates, shopped it without success to various studios before Oboler used it for this feature, which went into production with the title, The Lions of Gulu.[36] The critically panned film was nevertheless highly successful with audiences due to the novelty of 3D, which increased Hollywood interest in 3D during a period that had seen declining box-office admissions.[37]

As with practically all of the features made during this boom, Bwana Devil was projected dual-strip, with Polaroid filters. During the 1950s, the familiar disposable anaglyph glasses made of cardboard were mainly used for comic books, two shorts by exploitation specialist Dan Sonney, and three shorts produced by Lippert Productions. However, even the Lippert shorts were available in the dual-strip format alternatively.

Because the features utilized two projectors, the capacity limit of film being loaded onto each projector (about 6,000 feet (1,800 m), or an hour's worth of film) meant that an intermission was necessary for every feature-length film. Quite often, intermission points were written into the script at a major plot point.

During Christmas of 1952, producer Sol Lesser quickly premiered the dual-strip showcase called Stereo Techniques in Chicago.[38] Lesser acquired the rights to five dual-strip shorts. Two of them, Now is the Time (to Put On Your Glasses) and Around is Around, were directed by Norman McLaren in 1951 for the National Film Board of Canada. The other three films were produced in Britain for Festival of Britain in 1951 by Raymond Spottiswoode. These were A Solid Explanation, Royal River, and The Black Swan.

James Mage was also an early pioneer in the 3D craze. Using his 16 mm 3D Bolex system, he premiered his Triorama program on February 10, 1953, with his four shorts: Sunday In Stereo, Indian Summer, American Life, and This is Bolex Stereo.[39] This show is considered lost.

Another early 3D film during the boom was the Lippert Productions short, A Day in the Country, narrated by Joe Besser and composed mostly of test footage. Unlike all of the other Lippert shorts, which were available in both dual-strip and anaglyph, this production was released in anaglyph only.

April 1953 saw two groundbreaking features in 3D: Columbia'sMan in the Dark and Warner Bros.House of Wax, the first 3D feature with stereophonic sound. House of Wax, outside of Cinerama, was the first time many American audiences heard recorded stereophonic sound. It was also the film that typecast Vincent Price as a horror star as well as the "King of 3-D" after he became the actor to star in the most 3D features (the others were The Mad Magician, Dangerous Mission, and Son of Sinbad). The success of these two films proved that major studios now had a method of getting filmgoers back into theaters and away from television sets, which were causing a steady decline in attendance.

The Walt Disney Studios entered 3D with its May 28, 1953, release of Melody, which accompanied the first 3D western, Columbia's Fort Ti at its Los Angeles opening. It was later shown at Disneyland's Fantasyland Theater in 1957 as part of a program with Disney's other short Working for Peanuts, entitled, 3-D Jamboree. The show was hosted by the Mousketeers and was in color.

Universal-International released their first 3D feature on May 27, 1953, It Came from Outer Space, with stereophonic sound. Following that was Paramount's first feature, Sangaree with Fernando Lamas and Arlene Dahl.

Columbia released several 3D westerns produced by Sam Katzman and directed by William Castle. Castle would later specialize in various technical in-theater gimmicks for such Columbia and Allied Artists features as 13 Ghosts, House on Haunted Hill, and The Tingler. Columbia also produced the only slapstick comedies conceived for 3D. The Three Stooges starred in Spooks and Pardon My Backfire; dialect comic Harry Mimmo starred in Down the Hatch. Producer Jules White was optimistic about the possibilities of 3D as applied to slapstick (with pies and other projectiles aimed at the audience), but only two of his stereoscopic shorts were shown in 3D. Down the Hatch was released as a conventional, "flat" motion picture. (Columbia has since printed Down the Hatch in 3D for film festivals.)

John Ireland, Joanne Dru and Macdonald Carey starred in the Jack Broder color production Hannah Lee, which premiered June 19, 1953. The film was directed by Ireland, who sued Broder for his salary. Broder counter-sued, claiming that Ireland went over production costs with the film.[citation needed]

Another famous entry in the golden era of 3D was the 3 Dimensional Pictures production of Robot Monster. The film was allegedly scribed in an hour by screenwriter Wyott Ordung and filmed in a period of two weeks on a shoestring budget.[citation needed] Despite these shortcomings and the fact that the crew had no previous experience with the newly built camera rig, luck was on the cinematographer's side, as many find the 3D photography in the film is well shot and aligned. Robot Monster also has a notable score by then up-and-coming composer Elmer Bernstein. The film was released June 24, 1953, and went out with the short Stardust in Your Eyes, which starred nightclub comedian, Slick Slavin.[citation needed]

20th Century Fox produced their only 3D feature, Inferno in 1953, starring Rhonda Fleming. Fleming, who also starred in Those Redheads From Seattle, and Jivaro, shares the spot for being the actress to appear in the most 3D features with Patricia Medina, who starred in Sangaree, Phantom of the Rue Morgue and Drums of Tahiti. Darryl F. Zanuck expressed little interest in stereoscopic systems, and at that point was preparing to premiere the new widescreen film system, CinemaScope.

The first decline in the theatrical 3D craze started in August and September 1953. The factors causing this decline were:

- Two prints had to be projected simultaneously.[citation needed]

- The prints had to remain exactly alike after repair, or synchronization would be lost.[citation needed]

- It sometimes required two projectionists to keep sync working properly.[citation needed]

- When either prints or shutters became out of sync, even for a single frame, the picture became virtually unwatchable and accounted for headaches and eyestrain.[citation needed]

- The necessary silver projection screen was very directional and caused sideline seating to be unusable with both 3D and regular films, due to the angular darkening of these screens. Later films that opened in wider-seated venues often premiered flat for that reason (such as Kiss Me Kate at the Radio City Music Hall).[citation needed]

- A mandatory intermission was needed to properly prepare the theater's projectors for the showing of the second half of the film.[citation needed]

Because projection booth operators were at many times careless, even at preview screenings of 3D films, trade and newspaper critics claimed that certain films were "hard on the eyes."[citation needed]

Sol Lesser attempted to follow up Stereo Techniques with a new showcase, this time five shorts that he himself produced.[citation needed] The project was to be called The 3-D Follies and was to be distributed by RKO.[citation needed] Unfortunately, because of financial difficulties and the general loss of interest in 3D, Lesser canceled the project during the summer of 1953, making it the first 3D film to be aborted in production.[citation needed] Two of the three shorts were shot: Carmenesque, a burlesque number starring exotic dancer Lili St. Cyr, and Fun in the Sun, a sports short directed by famed set designer/director William Cameron Menzies, who also directed the 3D feature The Maze for Allied Artists.

Although it was more expensive to install, the major competing realism process was wide-screen, but two-dimensional, anamorphic, first utilized by Fox with CinemaScope and its September premiere in The Robe. Anamorphic films needed only a single print, so synchronization was not an issue. Cinerama was also a competitor from the start and had better quality control than 3D because it was owned by one company that focused on quality control. However, most of the 3D features past the summer of 1953 were released in the flat widescreen formats ranging from 1.66:1 to 1.85:1. In early studio advertisements and articles about widescreen and 3D formats, widescreen systems were referred to as "3D", causing some confusion among scholars.[citation needed]

There was no single instance of combining CinemaScope with 3D until 1960, with a film called September Storm, and even then, that was a blow-up from a non-anamorphic negative.[citation needed]September Storm also went out with the last dual-strip short, Space Attack, which was actually shot in 1954 under the title The Adventures of Sam Space.

In December 1953, 3D made a comeback with the release of several important 3D films, including MGM's musical Kiss Me, Kate. Kate was the hill over which 3D had to pass to survive. MGM tested it in six theaters: three in 3D and three flat.[citation needed] According to trade ads of the time, the 3D version was so well-received that the film quickly went into a wide stereoscopic release.[citation needed] However, most publications, including Kenneth Macgowan's classic film reference book Behind the Screen, state that the film did much better as a "regular" release. The film, adapted from the popular Cole PorterBroadway musical, starred the MGM songbird team of Howard Keel and Kathryn Grayson as the leads, supported by Ann Miller, Keenan Wynn, Bobby Van, James Whitmore, Kurt Kasznar and Tommy Rall. The film also prominently promoted its use of stereophonic sound.

Several other features that helped put 3D back on the map that month were the John Wayne feature Hondo (distributed by Warner Bros.), Columbia's Miss Sadie Thompson with Rita Hayworth, and Paramount's Money From Home with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. Paramount also released the cartoon shorts Boo Moon with Casper, the Friendly Ghost and Popeye, Ace of Space with Popeye the Sailor. Paramount Pictures released a 3D Korean War film Cease Fire filmed on actual Korean locations in 1953.[40]

Top Banana, based on the popular stage musical with Phil Silvers, was brought to the screen with the original cast. Although it was merely a filmed stage production, the idea was that every audience member would feel they would have the best seat in the house through color photography and 3D.[citation needed] Although the film was shot and edited in 3D, United Artists, the distributor, felt the production was uneconomical in stereoscopic form and released the film flat on January 27, 1954.[citation needed] It remains one of two "Golden era" 3D features, along with another United Artists feature, Southwest Passage (with John Ireland and Joanne Dru), that are currently considered lost (although flat versions survive).

A string of successful films filmed in 3D followed the second wave, but many were widely or exclusively shown flat. Some highlights are:

- The French Line, starring Jane Russell and Gilbert Roland, a Howard Hughes/RKO production. The film became notorious for being released without an MPAA seal of approval, after several suggestive lyrics were included, as well as one of Ms. Russell's particularly revealing costumes.[citation needed] Playing up her sex appeal, one tagline for the film was, "It'll knock both of your eyes out!" The film was later cut and approved by the MPAA for a general flat release, despite having a wide and profitable 3D release.[citation needed]

- Taza, Son of Cochise, a sequel to 1950s Broken Arrow, which starred Rock Hudson in the title role, Barbara Rush as the love interest, and Rex Reason (billed as Bart Roberts) as his renegade brother. Originally released flat through Universal-International. It was directed by the great stylist Douglas Sirk, and his striking visual sense made the film a huge success when it was "re-premiered" in 3D in 2006 at the Second 3D Expo in Hollywood.

- Two ape films: Phantom of the Rue Morgue, featuring Karl Malden and Patricia Medina, produced by Warner Bros. and based on Edgar Allan Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue", and Gorilla at Large, a Panoramic Production starring Cameron Mitchell, distributed flat and 3D through Fox.

- Creature from the Black Lagoon, starring Richard Carlson and Julie Adams, directed by Jack Arnold. Although arguably the most famous 3D film, it was typically seen in 3D only in large urban theaters and shown flat in the many smaller neighborhood theaters.[41] It was the only 3D feature that spawned a 3D sequel, Revenge of the Creature, which was in turn followed by The Creature Walks Among Us, shot flat.

- Dial M for Murder, directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Ray Milland, Robert Cummings, and Grace Kelly, is considered by aficionados of 3D to be one of the best examples of the process. Although available in 3D in 1954, there are no known playdates in 3D,[citation needed] since Warner Bros. had just instated a simultaneous 3D/2D release policy. The film's screening in 3D in February 1980 at the York Theater in San Francisco did so well that Warner Bros. re-released the film in 3D in February 1982. The film is now available on 3D Blu-ray, marking the first time it was released on home video in its 3D presentation.

- Gog, the last episode in Ivan Tors' Office of Scientific Investigation (OSI) trilogy dealing with realistic science fiction (following The Magnetic Monster and Riders to the Stars). Most theaters showed it flat.

- The Diamond (released in the United States as The Diamond Wizard), a 1954 British crime film starring Dennis O'Keefe. The only stereoscopic feature shot in Britain, released flat in both the UK and US.

- Irwin Allen's Dangerous Mission released by RKO in 1954 featuring Allen's trademarks of an all-star cast facing a disaster (a forest fire). Bosley Crowther's New York Times review mentions that it was shown flat.

- Son of Sinbad, another RKO/Howard Hughes production, starring Dale Robertson, Lili St. Cyr, and Vincent Price. The film was shelved after Hughes ran into difficulty with The French Line, and was not released until 1955, at which time it went out flat, converted to the SuperScope process.

3D's final decline was in the late spring of 1954, for the same reasons as the previous lull, as well as the further success of widescreen formats with theater operators. Even though Polaroid had created a well-designed "Tell-Tale Filter Kit" for the purpose of recognizing and adjusting out of sync and phase 3D,[citation needed] exhibitors still felt uncomfortable with the system and turned their focus instead to processes such as CinemaScope. The last 3D feature to be released in that format during the "Golden era" was Revenge of the Creature, on February 23, 1955. Ironically, the film had a wide release in 3D and was well received at the box office.[42]

Revival (1960–1984) in single strip format[edit]

Stereoscopic films largely remained dormant for the first part of the 1960s, with those that were released usually being anaglyph exploitation films. One film of notoriety was the Beaver-Champion/Warner Bros. production, The Mask (1961). The film was shot in 2-D, but to enhance the bizarre qualities of the dream-world that is induced when the main character puts on a cursed tribal mask, these scenes went to anaglyph 3D. These scenes were printed by Technicolor on their first run in red/green anaglyph.

Although 3D films appeared sparsely during the early 1960s, the true second wave of 3D cinema was set into motion by Arch Oboler, the producer who had started the craze of the 1950s. Using a new technology called Space-Vision 3D. The origin of "Space-Vision 3D" goes back to Colonel Robert Vincent Bernier, a forgotten innovator in the history of stereoscopic motion pictures. His Trioptiscope Space-Vision lens was the gold standard for the production and exhibition of 3-D films for nearly 30 years.[43] "Space-Vision 3D" stereoscopic films were printed with two images, one above the other, in a single academy ratio frame, on a single strip, and needed only one projector fitted with a special lens. This so-called "over and under" technique eliminated the need for dual projector set-ups, and produced widescreen, but darker, less vivid, polarized 3D images. Unlike earlier dual system, it could stay in perfect synchronization, unless improperly spliced in repair.

Arch Oboler once again had the vision for the system that no one else would touch, and put it to use on his film entitled The Bubble, which starred Michael Cole, Deborah Walley, and Johnny Desmond. As with Bwana Devil, the critics panned The Bubble, but audiences flocked to see it, and it became financially sound enough to promote the use of the system to other studios, particularly independents, who did not have the money for expensive dual-strip prints of their productions.

In 1970, Stereovision, a new entity founded by director/inventor Allan Silliphant and optical designer Chris Condon, developed a different 35 mm single-strip format, which printed two images squeezed side by side and used an anamorphic lens to widen the pictures through Polaroid filters. Louis K. Sher (Sherpix) and Stereovision released the softcore sex comedy The Stewardesses (self-rated X, but later re-rated R by the MPAA). The film cost US$100,000 to produce, and ran for months in several markets.[citation needed] eventually earning $27 million in North America, alone ($140 million in constant-2010 dollars) in fewer than 800 theaters, becoming the most profitable 3-Dimensional film to date, and in purely relative terms, one of the most profitable films ever. It was later released in 70 mm 3D. Some 36 films worldwide were made with Stereovision over 25 years, using either a widescreen (above-below), anamorphic (side by side) or 70 mm 3D formats.[citation needed] In 2009 The Stewardesses was remastered by Chris Condon and director Ed Meyer, releasing it in XpanD 3D, RealD Cinema and Dolby 3D.

The quality of the 1970s 3D films was not much more inventive, as many were either softcore and even hardcore adult films, horror films, or a combination of both. Paul Morrisey's Flesh For Frankenstein (aka Andy Warhol's Frankenstein) was a superlative example of such a combination.

Between 1981 and 1983 there was a new Hollywood 3D craze started by the spaghetti western Comin' at Ya!. When Parasite was released it was billed as the first horror film to come out in 3D in over 20 years. Horror films and reissues of 1950s 3D classics (such as Hitchcock's Dial M for Murder) dominated the 3D releases that followed. The second sequel in the Friday the 13th series, Friday the 13th Part III, was released very successfully. Apparently saying "part 3 in 3D" was considered too cumbersome so it was shortened in the titles of Jaws 3-D and Amityville 3-D, which emphasized the screen effects to the point of being annoying at times, especially when flashlights were shone into the eyes of the audience.

The science fiction film Spacehunter: Adventures in the Forbidden Zone was the most expensive 3D film made up to that point with production costs about the same as Star Wars but not nearly the same box office success, causing the craze to fade quickly through spring 1983. Other sci-fi/fantasy films were released as well including Metalstorm: The Destruction of Jared-Syn and Treasure of the Four Crowns, which was widely criticized for poor editing and plot holes, but did feature some truly spectacular closeups.

3D releases after the second craze included The Man Who Wasn't There (1983), Silent Madness and the 1985 animated film Starchaser: The Legend of Orin, whose plot seemed to borrow heavily from Star Wars.

Only Comin' At Ya!, Parasite, and Friday the 13th Part III have been officially released on VHS and/or DVD in 3D in the United States (although Amityville 3D has seen a 3D DVD release in the United Kingdom). Most of the 1980s 3D films and some of the classic 1950s films such as House of Wax were released on the now defunct Video Disc (VHD) format in Japan as part of a system that used shutter glasses. Most of these have been unofficially transferred to DVD and are available on the grey market through sites such as eBay.

Stereoscopic movies were also popular in other parts of the world, such as My Dear Kuttichathan, a Malayalam film which was shot with stereoscopic 3D and released in 1984.

Rebirth of 3D (1985–2003)[edit]

In the mid-1980s, IMAX began producing non-fiction films for its nascent 3D business, starting with We Are Born of Stars (Roman Kroitor, 1985). A key point was that this production, as with all subsequent IMAX productions, emphasized mathematical correctness of the 3D rendition and thus largely eliminated the eye fatigue and pain that resulted from the approximate geometries of previous 3D incarnations. In addition, and in contrast to previous 35mm-based 3D presentations, the very large field of view provided by IMAX allowed a much broader 3D "stage", arguably as important in 3D film as it is theatre.

The Walt Disney Company also began more prominent use of 3D films in special venues to impress audiences with Magic Journeys (1982) and Captain EO (Francis Ford Coppola, 1986, starring Michael Jackson) being notable examples. In the same year, the National Film Board of Canada production Transitions (Colin Low), created for Expo 86 in Vancouver, was the first IMAX presentation using polarized glasses. Echoes of the Sun (Roman Kroitor, 1990) was the first IMAX film to be presented using alternate-eye shutterglass technology, a development required because the dome screen precluded the use of polarized technology.

From 1990 onward, numerous films were produced by all three parties to satisfy the demands of their various high-profile special attractions and IMAX's expanding 3D network. Films of special note during this period include the extremely successful Into the Deep (Graeme Ferguson, 1995) and the first IMAX 3D fiction film Wings of Courage (1996), by director Jean-Jacques Annaud, about the pilot Henri Guillaumet.

Other stereoscopic films produced in this period include:

- The Last Buffalo (Stephen Low, 1990)

- Jim Henson's Muppet*Vision 3D (Jim Henson, 1991)

- Imagine (John Weiley, 1993)

- Honey, I Shrunk the Audience (Daniel Rustuccio, 1994)

- Into the Deep (Graeme Ferguson, 1995)

- Across the Sea of Time (Stephen Low, 1995)

- Wings of Courage (Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1996)

- L5, First City in Space (Graeme Ferguson, 1996)

- T2 3-D: Battle Across Time (James Cameron, 1996)

- Paint Misbehavin (Roman Kroitor and Peter Stephenson, 1997)

- IMAX Nutcracker (1997)

- The Hidden Dimension (1997)

- T-Rex: Back to the Cretaceous (Brett Leonard, 1998)

- Mark Twain's America (Stephen Low, 1998)

- Siegfried & Roy: The Magic Box (Brett Leonard, 1999)

- Galapagos (Al Giddings and David Clark, 1999)

- Encounter in the Third Dimension (Ben Stassen, 1999)

- Alien Adventure (Ben Stassen, 1999)

- Ultimate G's (2000)

- Cyberworld (Hugh Murray, 2000)

- Cirque du Soleil: Journey of Man (Keith Melton, 2000)

- Haunted Castle (Ben Stassen, 2001)

- Panda Vision (Ben Stassen, 2001)

- Space Station 3D (Toni Myers, 2002)

- SOS Planet (Ben Stassen, 2002)

- Ocean Wonderland (2003)

- Falling in Love Again (Munro Ferguson, 2003)

- Misadventures in 3D (Ben Stassen, 2003)

By 2004, 54% of IMAX theaters (133 of 248) were capable of showing 3D films.[44]

Shortly thereafter, higher quality computer animation, competition from DVDs and other media, digital projection, digital video capture, and the use of sophisticated IMAX 70mm film projectors, created an opportunity for another wave of 3D films.[45][46]

Mainstream resurgence (2003–present)[edit]

In 2003, Ghosts of the Abyss

Because you are going to have more detractors than Nicolaus Copernicus when he wanted to displace the Earth from the center of the universe. - Preceding unsigned comment added by 2. 137. 153. 245 (talk) 19:35, 13 August 2011 (UTC)ph3Another moveh3pPer WP:NCDAB: pblockquotepIf there are several possible choices for disambiguating with a class or context, use the same disambiguating phrase already commonly used for other topics within the same class and context, if any.

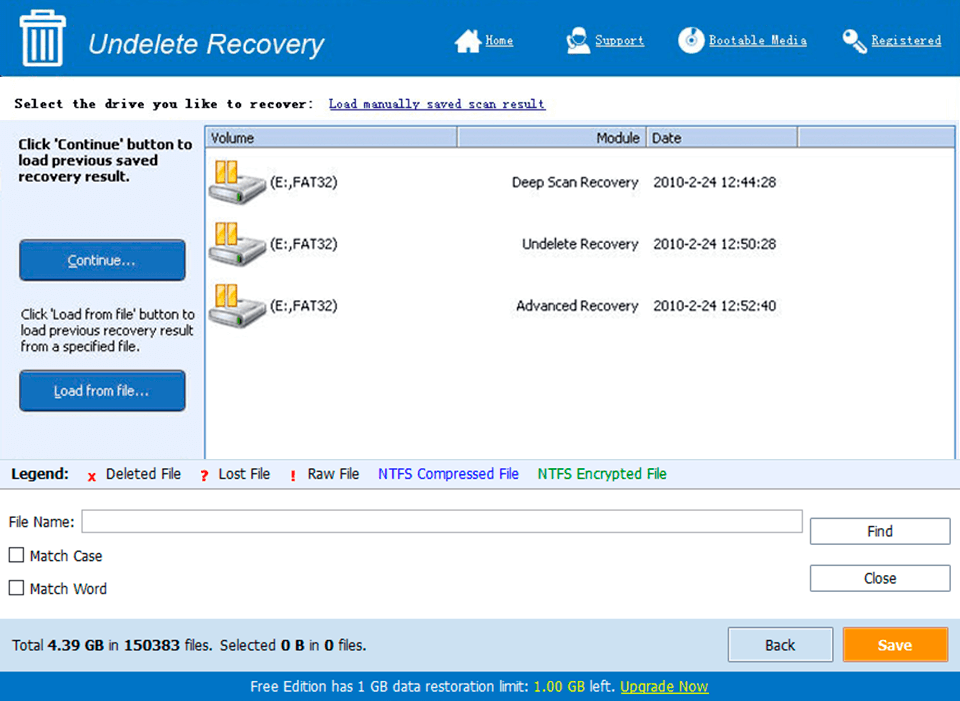

.What’s New in the Stereoscopic Player (Commercial License) 1.6.2 serial key or number?

Screen Shot

System Requirements for Stereoscopic Player (Commercial License) 1.6.2 serial key or number

- First, download the Stereoscopic Player (Commercial License) 1.6.2 serial key or number

-

You can download its setup from given links: