Red Alchemist Pro v1.1 Red Alert Editor serial key or number

Red Alchemist Pro v1.1 Red Alert Editor serial key or number

Orange (colour)

| Orange | |

|---|---|

| Spectral coordinates | |

| Wavelength | 590–620 nm |

| Frequency | 505–480 THz |

Colour coordinates Colour coordinates | |

| Hex triplet | #FF7F00 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (255, 127, 0) |

| CMYKH (c, m, y, k) | (0, 50, 100, 0) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (30°, 100%, 100%) |

| Source | HTML Colour Chart @30 |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Orange is the colour between yellow and red on the spectrum of visible light. Human eyes perceive orange when observing light with a dominant wavelength between roughly 585 and 620 nanometres. In painting and traditional colour theory, it is a secondary colour of pigments, created by mixing yellow and red. It is named after the fruit of the same name.

The orange colour of carrots, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, oranges, and many other fruits and vegetables comes from carotenes, a type of photosynthetic pigment. These pigments convert the light energy that the plants absorb from the sun into chemical energy for the plants' growth. Similarly the hues of autumn leaves are from the same pigment after chlorophyll is removed.

In Europe and America, surveys show that orange is the colour most associated with amusement, the unconventional, extroverts, warmth, fire, energy, activity, danger, taste and aroma, the autumn and Allhallowtide seasons, as well as having long been the national color of the Netherlands and the House of Orange. It also serves as the political colour of Christian democracy political ideology and most Christian democratic political parties.[1] In Asia it is an important symbolic colour of Buddhism and Hinduism.[2]

In nature and culture[edit]

Etymology[edit]

In English, the colour orange is named after the appearance of the ripe orange fruit.[3] The word comes from the Old French orange, from the old term for the fruit, pomme d'orange. The French word, in turn, comes from the Italian arancia,[4][5] based on Arabic nāranj (نارنج), derived from the Sanskritnāraṅga (नारङ्ग), which in turn derives from a Dravidian root word (compare நரந்தம் narandam which refers to Bitter orange in Tamil).[6] The earliest known recorded use of orange as a colour name in English was in 1502, in a description of clothing purchased for Margaret Tudor.[7][8] Another early recorded use was in 1512,[9][10] in a will now filed with the Public Record Office. The place-name "Orange" has a separate etymology and is not related to that of the colour.[11]

Prior to this word's being introduced to the English-speaking world, saffron already existed in the English language.[12]Crog also referred to the saffron colour, so that orange was also referred to as ġeolurēad (yellow-red) for reddish orange, or ġeolucrog (yellow-saffron) for yellowish orange.[13][14][15] Alternatively, orange things were sometimes described as red such as red deer, red hair, the Red Planet and robin redbreast.

History and art[edit]

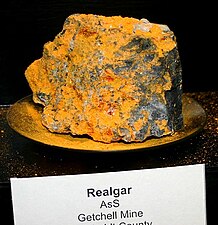

In ancient Egypt, artists used an orange mineral pigment called realgar for tomb paintings, as well as other uses. It was also used later by Medieval artists for the colouring of manuscripts. Pigments were also made in ancient times from a mineral known as orpiment. Orpiment was an important item of trade in the Roman Empire and was used as a medicine in China although it contains arsenic and is highly toxic. It was also used as a fly poison and to poison arrows. Because of its yellow-orange colour, it was also a favourite with alchemists searching for a way to make gold, both in China and in the West.

Before the late 15th century, the colour orange existed in Europe, but without the name; it was simply called yellow-red. Portuguese merchants brought the first orange trees to Europe from Asia in the late 15th and early 16th century, along with the Sanskrit naranga, which gradually became part of several European languages: "naranja" in Spanish, "laranja" in Portuguese, and "orange" in English.

People in ancient Egyptian wall paintings often were shown with orange or yellow-orange skin, painted with a pigment called realgar.

The mineral orpiment was a source of yellow and orange pigments in ancient Rome, though it contained arsenic and was highly toxic.

House of Orange[edit]

The House of Orange-Nassau was one of the most influential royal houses in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. It originated in 1163 the tiny Principality of Orange, a feudal state of 108 square miles (280 km2) north of Avignon in southern France. The Principality of Orange took its name not from the fruit, but from a Roman-Celtic settlement on the site which was founded in 36 or 35 BC and was named Arausio, after a Celticwater god;[16] however, the name may have been slightly altered, and the town associated with the colour, because it was on the route by which quantities of oranges were brought from southern ports such as Marseille to northern France.

The family of the Prince of Orange eventually adopted the name and the colour orange in the 1570s.[17] The colour came to be associated with Protestantism, due to participation by the House of Orange on the Protestant side in the French Wars of Religion. One member of the house, William I of Orange, organised the Dutch resistance against Spain, a war that lasted eighty years, until the Netherlands won its independence. The House's arguably most prominent member, William III of Orange, became King of England in 1689, after the downfall of the Catholic James II.

Due to William III, orange became an important political colour in Britain and Europe. William was a Protestant, and as such he defended the Protestant minority of Ireland against the majority Roman Catholic population. As a result, the Protestants of Ireland were known as Orangemen. Orange eventually became one of the colours of the Irish flag, symbolising the Protestant heritage. His rebel flag became the forerunner of The Netherlands' modern flag.[17]

When the Dutch settlers of British Cape Colony (now part of South Africa) migrated against the British in the 19th century, they founded what they called the Orange Free State. In the United States, the flag of the City of New York has an orange stripe, to remember the Dutch colonists who founded the city. William of Orange is also remembered as the founder of the College of William & Mary, and Nassau County in New York is named after the House of Orange-Nassau.

18th and 19th century[edit]

In the 18th century orange was sometimes used to depict the robes of Pomona, the goddess of fruitful abundance; her name came from the pomon, the Latin word for fruit. Oranges themselves became more common in northern Europe, thanks to the 17th century invention of the heated greenhouse, a building type which became known as an orangerie. The French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard depicted an allegorical figure of "inspiration" dressed in orange.

In 1797 a French scientist Louis Vauquelin discovered the mineral crocoite, or lead chromate, which led in 1809 to the invention of the synthetic pigment chrome orange. Other synthetic pigments, cobalt red, cobalt yellow, and cobalt orange, the last made from cadmium sulfide plus cadmium selenide, soon followed. These new pigments, plus the invention of the metal paint tube in 1841, made it possible for artists to paint outdoors and to capture the colours of natural light.

In Britain orange became highly popular with the Pre-Raphaelites and with history painters. The flowing red-orange hair of Elizabeth Siddal, a prolific model and the wife of painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, became a symbol of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, Lord Leighton, the president of the Royal Academy, produced Flaming June, a painting of a sleeping young woman in a bright orange dress, which won wide acclaim. Albert Joseph Moore painted festive scenes of Romans wearing orange cloaks brighter than any the Romans ever likely wore. In the United States, Winslow Homer brightened his palette with vivid oranges.

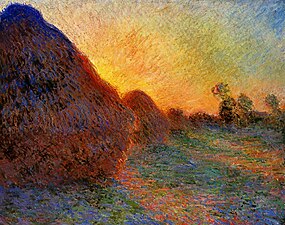

In France painters took orange in an entirely different direction. In 1872 Claude Monet painted Impression, Sunrise, a tiny orange sun and some orange light reflected on the clouds and water in the centre of a hazy blue landscape. This painting gave its name to the impressionist movement.

Orange became an important colour for all the impressionist painters. They all had studied the recent books on colour theory, and they know that orange placed next to azure blue made both colours much brighter. Auguste Renoir painted boats with stripes of chrome orange paint straight from the tube. Paul Cézanne did not use orange pigment, but created his own oranges with touches of yellow, red and ochre against a blue background. Toulouse-Lautrec often used oranges in the skirts of dancers and gowns of Parisiennes in the cafes and clubs he portrayed. For him it was the colour of festivity and amusement.

The post-impressionists went even further with orange. Paul Gauguin used oranges as backgrounds, for clothing and skin colour, to fill his pictures with light and exoticism. But no other painter used orange so often and dramatically as Vincent van Gogh. who had shared a house with Gauguin in Arles for a time. For Van Gogh orange and yellow were the pure sunlight of Provence. He created his own oranges with mixtures of yellow, ochre and red, and placed them next to slashes of sienna red and bottle green, and below a sky of turbulent blue and violet. He put an orange moon and stars in a cobalt blue sky. He wrote to his brother Theo of "searching for oppositions of blue with orange, of red with green, of yellow with violet, searching for broken colours and neutral colours to harmonize the brutality of extremes, trying to make the colours intense, and not a harmony of greys."[18]

Oarsmen at Chatou by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1879). Renoir knew that orange and blue brightened each other when put side by side.

Willow trees at sunset by Van Gogh, Arles (1888)

Meules, from the 1890–1891 series of Haystacks by Claude Monet

20th and 21st centuries[edit]

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the colour orange had highly varied associations, both positive and negative.

The high visibility of orange made it a popular colour for certain kinds of clothing and equipment. During the Second World War, US Navy pilots in the Pacific began to wear orange inflatable life jackets, which could be spotted by search and rescue planes. After the war, these jackets became common on both civilian and naval vessels of all sizes, and on aircraft flown over water. Orange is also widely worn (to avoid being hit) by workers on highways and by cyclists.

A herbicide called Agent Orange was widely sprayed from aircraft by the Royal Air Force during the Malayan Emergency and the US Air Force during the Vietnam War to remove the forest and jungle cover beneath which enemy combatants were believed to be hiding, and to expose their supply routes. The chemical was not actually orange, but took its name from the colour of the steel drums in which it was stored. Agent Orange was toxic, and was later linked to birth defects and other health problems.

Orange also had and continues to have a political dimension. Orange serves as the colour of Christian democratic political ideology, which is based on Catholic social teaching and Neo-Calvinist theology; Christian democratic political parties came to prominence in Europe and the Americas after World War II.[19][1]

In Ukraine in November–December 2004, it became the colour of the Orange Revolution, a popular movement which carried activist and reformer Viktor Yushchenko into the presidency.[20] In parts of the world, especially Northern Ireland, the colour is associated with the Orange Order, a Protestant fraternal organisation and relatedly, Orangemen, marches and other social and political activities, with the colour orange being associated with Protestantism similar to the Netherlands.

Science[edit]

Optics[edit]

In optics, orange is the colour seen by the eye when looking at light with a wavelength between approximately 585–620 nm. It has a hue of 30° in HSV colour space.

In the traditional colour wheel used by painters, orange is the range of colours between red and yellow, and painters can obtain orange simply by mixing red and yellow in various proportions; however these colours are never as vivid as a pure orange pigment. In the RGB colour model (the system used to create colours on a television or computer screen), orange is generated by combining high intensity red light with a lower intensity green light, with the blue light turned off entirely. Orange is a tertiary colour which is numerically halfway between gamma-compressed red and yellow, as can be seen in the RGB colour wheel.

Regarding painting, blue is the complementary colour to orange. As many painters of the 19th century discovered, blue and orange reinforce each other. The painter Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo that in his paintings, he was trying to reveal "the oppositions of blue with orange, of red with green, of yellow with violet ... trying to make the colours intense and not a harmony of grey".[21] In another letter he wrote simply, "there is no orange without blue."[22] Van Gogh, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and many other impressionist and post-impressionist painters frequently placed orange against azure or cobalt blue, to make both colours appear brighter.

The actual complement of orange is azure – a colour that is one quarter of the way between blue and green on the colour spectrum. The actual complementary colour of true blue is yellow. Orange pigments are largely in the ochre or cadmium families, and absorb mostly greenish-blue light.

(See also shades of orange).

Pigments and dyes[edit]

A sample of orpiment from an arsenic mine in southern Russia. Orpiment has been used to make orange pigment since ancient times in ancient Egypt, Europe and China. Romans used the mineral for trade.

Realgar, an arsenic sulfide mineral 1.5-2.5 Mohs hardness, is highly toxic. It was used since ancient times until the 19th century to make red-orange pigment, as a poison, and a medicine.

The Curcuma longa plant is used to make turmeric, a common and less expensive substitute for saffron as a dye and colour.

Other orange pigments include:

- Minium and massicot are bright yellow and orange pigments made since ancient times by heating lead oxide and its variants. Minium was used in the Byzantine Empire for making the red-orange colour on illuminated manuscripts, while massicot was used by ancient Egyptian scribes and in the Middle Ages. Both substances are toxic, and were replaced in the beginning of the 20th century by chrome orange and cadmium orange.[23]

- Cadmium orange is a synthetic pigment made cadmium sulfide. It is a by-product of mining for zinc, but also occurs rarely in nature in the mineral greenockite. It is usually made by replacing some of the sulphur with selenium, which results in an expensive but deep and lasting colour. Selenium was discovered in 1817, but the pigment was not made commercially until 1910.[24]

- Quinacridone orange is a synthetic organic pigment first identified in 1896 and manufactured in 1935. It makes a vivid and solid orange.

- Diketo-pyrrolo pyrolle orange or DPP orange is a synthetic organic pigment first commercialised in 1986. It is sold under various commercial names, such as translucent orange. It makes an extremely bright and lasting orange, and is widely used to colour plastics and fibres, as well as in paints.[25]

Orange natural objects[edit]

The orange colour of carrots, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, oranges, and many other fruits and vegetables comes from carotenes, a type of photosynthetic pigment. These pigments convert the light energy that the plants absorb from the sun into chemical energy for the plants' growth. The carotenes themselves take their name from the carrot.[26]Autumn leaves also get their orange colour from carotenes. When the weather turns cold and production of green chlorophyll stops, the orange colour remains.

Before the 18th century, carrots from Asia were usually purple, while those in Europe were either white or red. Dutch farmers bred a variety that was orange; according to some sources, as a tribute to the stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland, William of Orange.[27] The long orange Dutch carrot, first described in 1721, is the ancestor of the orange horn carrot, one of the most common types found in supermarkets today. It takes its name from the town of Hoorn, in the Netherlands.

Flowers[edit]

Orange is traditionally associated with the autumn season, with the harvest and autumn leaves. The flowers, like orange fruits and vegetables and autumn leaves, get their colour from the photosynthetic pigments called carotenes.

Creations of Fire

Introduction

he history of chemistry is a story of human endeavor-and as er T ratic as human nature itself. Progress has been made in fits and starts, and it has come from all parts of the globe. Because the scope of this history is considerable (some 100,000 years), it is necessary to impose some order, and we have organized the text around three dis cemible-albeit gross--divisions of time: Part 1 (Chaps. 1-7) covers 100,000 BeE (Before Common Era) to the late 1700s and presents the background of the Chemical Revolution; Part 2 (Chaps. 8-14) covers the late 1700s to World War land presents the Chemical Revolution and its consequences; Part 3 (Chaps. 15-20) covers World War I to 1950 and presents the Quantum Revolution and its consequences and hints at revolutions to come. There have always been two tributaries to the chemical stream: experiment and theory. But systematic experimental methods were not routinely employed until the 1600s-and quantitative theories did not evolve until the 1700s-and it can be argued that modem chernistry as a science did not begin until the Chemical Revolution in the 1700s. xi xii PREFACE We argue however that the first experiments were performed by arti sans and the first theories proposed by philosophers-and that a rev olution can be understood only in terms of what is being revolted against.

Keywords

biochemistry chemistry experiment inorganic chemistry kinetics organic chemistry polymer quantum chemistry radiochemistry thermodynamics

Bibliographic information

- DOIhttps://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2770-5

- Copyright InformationSpringer Science+Business Media New York 1995

- Publisher NameSpringer, Boston, MA

- eBook PackagesSpringer Book Archive

- Print ISBN978-0-306-45087-7

- Online ISBN978-1-4899-2770-5

- Buy this book on publisher's site

Alchemy: The Surprising Power of Ideas That Don't Make Sense

‘A breakthrough book. Wonderfully applicable to everything in life, and funny as hell.’ Nassim Nicholas Taleb

To be brilliant, you have to be irrational

Why is Red Bull so popular – even though everyone hates the taste? Why do countdown boards on platforms take away the pain of train delays? And why do we prefer stripy toothpaste?

We think we are rational creatures. Economics‘A breakthrough book. Wonderfully applicable to everything in life, and funny as hell.’ Nassim Nicholas Taleb

To be brilliant, you have to be irrational

Why is Red Bull so popular – even though everyone hates the taste? Why do countdown boards on platforms take away the pain of train delays? And why do we prefer stripy toothpaste?

We think we are rational creatures. Economics and business rely on the assumption that we make logical decisions based on evidence.

But we aren’t, and we don’t.

In many crucial areas of our lives, reason plays a vanishingly small part. Instead we are driven by unconscious desires, which is why placebos are so powerful. We are drawn to the beautiful, the extravagant and the absurd – from lavish wedding invitations to tiny bottles of the latest fragrance. So if you want to influence people’s choices you have to bypass reason. The best ideas don’t make rational sense: they make you feel more than they make you think.

Rory Sutherland is the Ogilvy advertising legend whose TED Talks have been viewed nearly 7 million times. In his first book he blends cutting-edge behavioural science, jaw-dropping stories and a touch of branding magic, on his mission to turn us all into idea alchemists. The big problems we face every day, whether as an individual or in society, could very well be solved by letting go of logic and embracing the irrational....more

Paperback, 384 pages

Published May 9th 2019 by WH Allen (first published 2019)

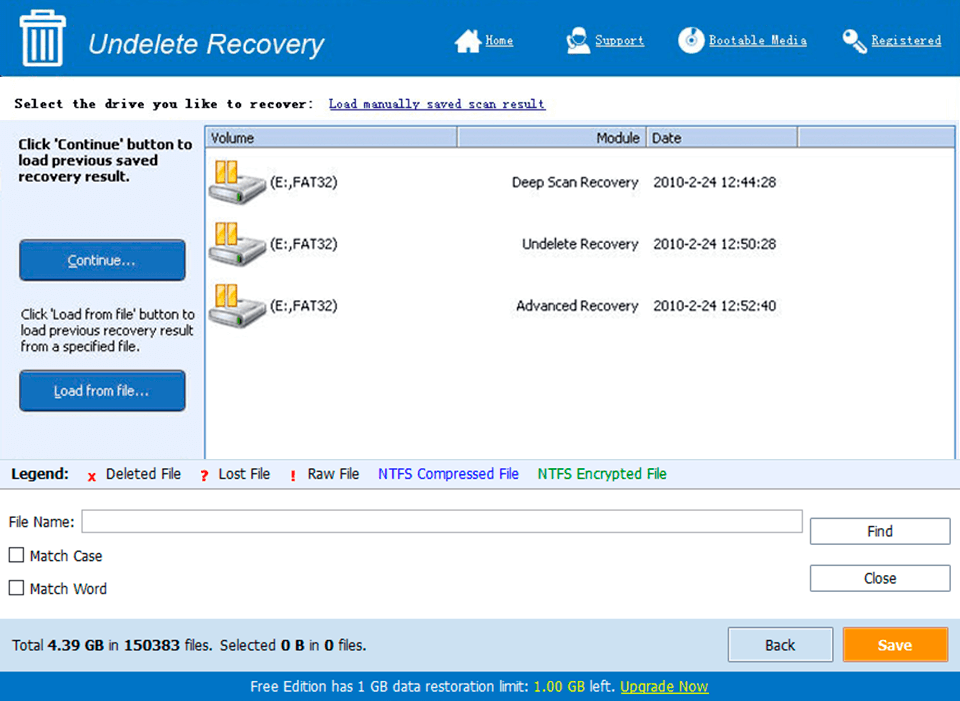

What’s New in the Red Alchemist Pro v1.1 Red Alert Editor serial key or number?

Screen Shot

System Requirements for Red Alchemist Pro v1.1 Red Alert Editor serial key or number

- First, download the Red Alchemist Pro v1.1 Red Alert Editor serial key or number

-

You can download its setup from given links: